Earth

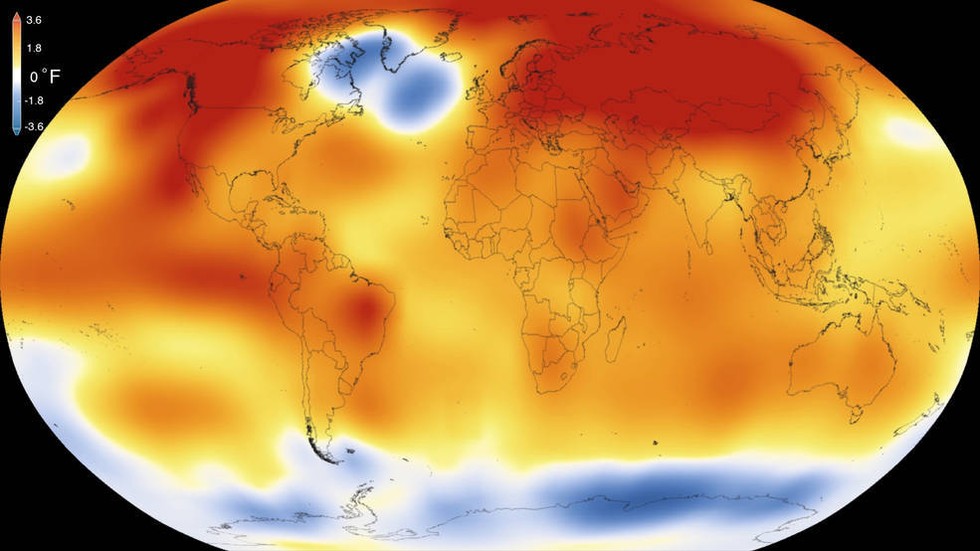

2015 was the warmest year since modern record-keeping began in 1880, according to a new analysis by NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies. The record-breaking year continues a long-term warming trend — 15 of the 16 warmest years on record have now occurred since 2001.

Earth is the warmest it’s been in 100,000 years, a new reconstruction of historical temperature data finds, and with today’s level of fossil fuel emissions the planet is “locked into” eventually hitting its highest temperature mark in 2 million years.

The new research published Monday in Nature was done by Carolyn Snyder, now a climate policy official at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, as a part of her doctoral dissertation at Stanford University, according to the Associated Press (AP).

Snyder “created a continuous 2 million year temperature record, much longer than a previous 22,000 year record. [Snyder’s reconstruction] doesn’t estimate temperature for a single year, but averages 5,000-year time periods going back a couple million years,” AP reported.

“We do find this close relationship between temperature and greenhouse gases that is remarkably stable, and what the study is developing is the coupling factor between the two,” Snyder told National Geographic.

AP further reports:

Temperatures averaged out over the most recent 5,000 years—which includes the last 125 years or so of industrial emissions of heat-trapping gases—are generally warmer than they have been since about 120,000 years ago or so, Snyder found. And two interglacial time periods, the one 120,000 years ago and another just about 2 million years ago, were the warmest Snyder tracked. They were about 3.6 degrees (2 degrees Celsius) warmer than the current 5,000-year average.

With the link to carbon dioxide levels and taking into account other factors and past trends, Snyder calculated how much warming can be expected in the future.

“Snyder said if climate factors are the same as in the past—and that’s a big if,” AP noted, “Earth is already committed to another 7 degrees or so (about 4 degrees Celsius) of warming over the next few thousand years.”

Nature described Snyder’s findings in greater detail in an article accompanying her published study:

“Even if the amount of atmospheric CO2 were to stabilize at current levels, the study suggests that average temperatures may increase by roughly 5 degrees C over the next few millennia as a result of the effects of the greenhouse gas on glaciers, ecosystems and other factors. A doubling of the pre-industrial levels of atmospheric CO2 of roughly 280 parts per million, which could occur within decades unless people curb greenhouse-gas emissions, could eventually boost global average temperatures by around 9 degrees C.”

Scripps Institute of Oceanography Mauna Loa Observatory / Climate Central

“This is not an exact prediction or a forecast,” Snyder told Nature, advising caution regarding her study’s temperature predictions. “The experiment we as humans are doing is very different than what we saw in the past.”

There has been some controversy in the scientific community following publication of Snyder’s research: several climate scientists told National Geographic that they felt Snyder’s estimate of future temperature rise, far higher than many previous estimates, was an outlier, signaling that her methods were faulty.

Michael Mann, an influential climate researcher at Penn State University who was not involved in Snyder’s research, told Mashable that “I regard the study as provocative and interesting, but the quantitative findings must be viewed rather skeptically until the analysis has been thoroughly vetted by the scientific community.”

Other scientists said they were intrigued by Snyder’s findings and hope her study leads to additional research. Jeremy Shakun, a climate researcher at Boston College, told AP that “Snyder’s work is a great contribution and future work should build on it.”

“It’s a useful starting place,” Snyder said to Nature about her research. “People can take this and improve upon it as more records become available in the future.”

WhosGreenOnline.com Your Online Magazine and Directory for Green Business, Product, Service and News!

WhosGreenOnline.com Your Online Magazine and Directory for Green Business, Product, Service and News!